The Epic of Gilgamesh: Lost and Found

by Chris Mack

December 8, 2018

The Epic of Gilgamesh is sometimes described as

the world’s first great work of literature.

But the story of how that poem came to be lost and then

rediscovered after 2500 years is itself an epic, if somewhat less

grandiose.

Gilgamesh is thought by scholars to have been

an historical figure, king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk during

the 27th century BCE.

Uruk was a major city, with 50,000 – 80,000 residents at its

height around 2900 BCE.

The earliest texts from Uruk date to 3300 BCE.

The city was located about 100 miles south of present-day

Bagdad, near the Euphrates River.

Uruk is thought to be the city of Erech mentioned in Genesis

and is sometimes referred to as “the first city in human history.”

|

|

|

Excavations in Uruk (source:

Wikipedia). |

Discovered by British archeologist William

Loftus in 1849 and first excavated in 1850-1854, the city was one of

the largest in the Sumerian and Babylonian eras, with an area of

over 2 square miles.

One of its distinguishing archeological features is the large

surrounding wall whose construction was attributed to Gilgamesh by

later ancient writers and referred to in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh is mentioned in the Sumerian King

list, an ancient stone tablet that provides a chronical of the kings

of Sumer through about 1700 BCE.

His place in the list occupies an interesting point of

transition from the legendary to the historical.

Before Gilgamesh every king is recorded as reigning for over

100 years, some for the tens of thousands of years.

After Gilgamesh, dynasties lasted from 3 to 36 years and this

portion of the list has been proven to be historically accurate.

Gilgamesh is listed as having ruled for 126 years, and thus

seems to represent the last of the god-like kings.

|

|

|

Cuneiform writing (source:

Wikipedia). |

The Sumerian civilization dates to about 5000

BCE, disappearing in about 1700 BCE after the rise of Babylonia.

Much of what we know about Sumer comes from cuneiform texts

written on clay tablets.

Cuneiform (the name means “wedged shape”) is one of the

earliest forms of writing, invented by the Sumerians in about 3000

BCE.

Writing became increasingly common during the

centuries around when Gilgamesh ruled.

King Shulgi of Ur (30 miles south of Uruk, reign 2094 – 2047

BCE) became the first major patron of literature, commissioning a

series of Sumerian poems about the exploits of Gilgamesh, probably

based on even earlier works.

These poems eventually became the basis for the original

Babylonian version of the Gilgamesh epic.

Fragments of the Epic of Gilgamesh has been

found in 14 cities around the Near East, and traveling performers

likely told the epic during the same time period as the early days

of the Homeric epics.

The first version of the Epic of Gilgamesh was written in about 2000

BCE. The flood story is

thought to have been added to the epic at around 1200 BCE based on

earlier Sumerian flood tales.

The oldest Sumerian flood story, with many of the same

elements as found in the Epic of Gilgamesh, was discovered at Nippur

and dates from 1600 BCE.

North of Sumer the Assyrian Empire rose from

the city-sate of Assur (Ashur) on the Tigris River in northern Iraq

starting around 2600 BCE. Assyria

grew to be an impressive empire that stretched from western Iran to

Egypt, and from southern Turkey to northern Saudi Arabia.

Tiglath-Pileser III (reign 745-727 BCE) created the world’s

first professional army and conquered most of the Near East.

While the formal language of the Assyrian Empire was

Akkadian, Tiglath-Pileser III established Aramaic as the de facto

language of the people throughout the empire.

Assyria conquered Israel in 710 BCE and conquered Egypt and

Babylon multiple times in this era.

This great empire collapsed with the fall of Nineveh in 612

BCE.

Central to the story of the Epic of Gilgamesh

as we know it today is the rule of King Ashurbanipal (reign 669 –

627 BCE). The capital

of Assyria was moved to Nineveh, just east of present-day Mosul in

Iraq, by Ashurbanipal’s grandfather and it quickly grew to be the

largest city in the world (>100,000 residents).

Ashurbanipal was a rare king who learned to both read and

write in multiple languages (rather than relying on scribes for this

specialized skill as did most kings).

He built a great library and spent much of his life

collecting and copying the great works of literature of his day.

Records indicate that Ashurbanipal acquired one copy the Epic

of Gilgamesh (written in Akkadian) in 647 BCE.

It is from this library that the Epic of Gilgamesh will

eventually be found.

Like many empires, overextension eventually led

to Assyria’s downfall.

Instability followed Ashurbanipal’s death, with Babylonia declaring

independence shortly after.

Rebels from Babylonia to the south and Persia to the east

eventually attacked Ninevah, and the capital fell in 612 BCE.

The fiery end to the palaces of Ashurbanipal left the library

collapsed and in ruin.

Ironically, though, it was the dramatic destruction of the library

that led to the preservation of its works.

Broken tablets from tens of thousands of books lay buried

under the rubble of Nineveh for the next 2500 years.

Found

The city of Nineveh was rediscovered by the

British Archeologist Austen Layard in 1840.

It was a formless mound of dirt 40 feet high and a mile wide

that had remained lost for over two millennia.

Excavating with his assistant Hormuzd Rassam, a native of

Mosul, Ashurbanipal’s library was discovered in 1853 and eventually

twenty-five thousand tablets would be sent to the British Museum.

But nobody could read them, since cuneiform writing was only

then being deciphered, and Akkadian could not yet be translated.

Cuneiform was decoded in the mid-19th

century when French scholar Eug�ne Burnouf discovered that it

contained an alphabet of 30 letters.

Akkadian began to be understood when British polymath Henry

Rawlinson translated the Behistun Inscription (the equivalent of the

Rosetta stone for the Egyptian language) and found that the language

was made up of about 600 phonetic syllables written in cuneiform

combined to create words.

Over a period of twenty years after the discovery of the

Ashurbanipal library the Akkadian language began to be translated.

|

|

|

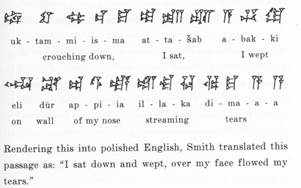

Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet 11: Story of the Flood.(source:

Wikipedia). |

An assistant curator at the British Museum,

George Smith, was slowly working through the many tablet fragments

found in Nineveh when in 1872 he came across a fragment of the flood

story from the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Parallels to the Biblical story of Noah were immediately

obvious and electrified Smith.

In December of that year he gave a lecture at the Biblical

Archeology Society in London, attended by Prime Minister William

Gladstone, and his discovery became an instant sensation.

All of a sudden these obscure tablets from an obscure era of

history became the talk of the nation.

Smith would eventually be sent to Iraq three

times where he found many of the missing pieces of the Epic of

Gilgamesh, including the missing parts of the flood story.

He published his translation of the flood story in 1875, and

died of dysentery in Allepo in 1876 at age 36 while returning from

his last archeological dig.

|

|

|

Translation of a portion of Table 11, Epic of Gilgamesh

(source: David

Damrosch 2006). |

The Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh

remains incomplete.

Only about 2,000 out of the poem’s 3,000 lines have been discovered.

David Damrosch, “The Buried Book: the Loss and

Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh”, Henry Holt and Co., New

York (2006).

Alexander Heidel, “The Gilgamesh Epic and Old

Testament Parallels”, University of Chicago Press (1945).

Chris Mack is a writer in Austin, Texas.

© Copyright 2018, Chris Mack.

More essays...